“The book says: We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us.”

– Jimmy Gator / Quiz Kid Donnie Smith / Narrator

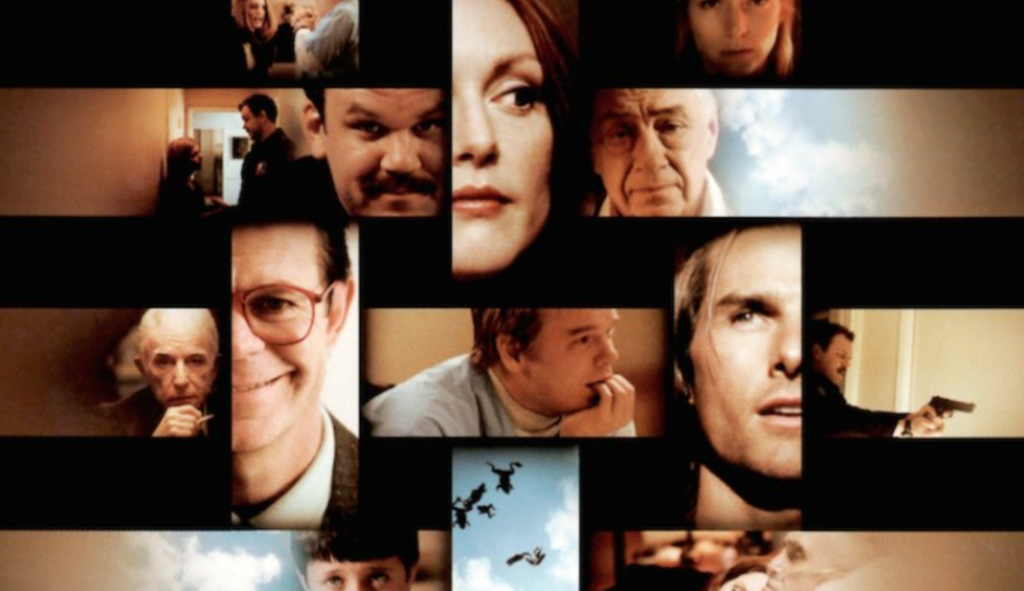

I’m pretty sure Anderson cringes at this movie. And I do too, honestly. The above quote can seem faux-deep when isolated and presented at the top of a semi-critical analysis like this one. It seems a bit trite. Overly melodramatic. Especially when the phrase itself is used not once, not twice, but three times in the film. By two different characters and the narrator. When Jimmy Gator says it, it’s almost hidden. In his preoccupied state of self-grieving, we almost miss it. There’s so much else going on, both in the film and in his own mind, that it almost seems thrown away. Just something that bubbles to the surface from some long-forgotten experience that, by the time it reaches his consciousness, has lost all its original meaning. But once it leaves his lips, it becomes real again. And it scares him. By the time the former quiz kid says it, we’ve already picked up on its importance, however vague it may be. It’s awkward. Is this some kind of shared experience? Jimmy and Donnie would have known each other in the past. Is there some connection there? The statement itself is in-your-face and brash. It dares you to defy it. And frustratingly, you can’t. Because it’s true. Maddeningly true. And maybe that’s why it’s uncomfortable to hear. Maybe that’s why it makes us cringe – not because of how cliche it initially sounds. This kind of dilemma is what Magnolia is all about. Being confronted by something scary, or true, or more often both, and then trying to hide behind personal platitudes and identities built up over years of abuse or expectation or something else. It’s about how the events of one’s life are both random and connected, somehow at the same time.

Frank TJ Mackey (Tom Cruise) may be the best embodiment of this dilemma. Desperate to change his own history in order to improve his present (at the expense of his future), Frank builds what he believes to be a fortified castle of forgetting. By turning into the worst possible version of himself, he’s unwittingly set himself up for a massive collapse of his psyche. However tough the exterior, he’s soft inside. He’s still the boy, alone, caring for his sick mother. And once the exterior shell is punctured (first by the TV reporter, then ripped wide open by Phil the nurse, played beautifully by Philip Seymour Hoffman), he’s left with nothing to defend himself from his own fractured id. The ego of his constructed persona is large, and ugly. But it melts like butter when confronted with the one thing he’s always wanted and feared: his father’s acknowledgement. His story is tragic no matter what (for both his character and the audience). It was always destined to be, as the narrator would have you believe.

I’m sure I could put all the characters in this prism, and break down what part of them is broken inside, and how the events of this movie either destroy them or save them. But I won’t. There’s more than enough to chew on here. Hidden Easter eggs and clues (8:2). For the curious, there are scores of fan essays out there to try and tear into this movie’s themes and hidden meanings. But at a certain point, you just have to acquiesce to its emotions, rather than read too much into its mythology and structure.

Another thing that intrigues me about PT is how he handles his scores. The whole first act is mostly underscored by the same rising and falling song. It’s tense and haunting, and beautiful. Now would be a good time as any to talk about Jon Brion’s role in Anderson’s early career. Brion composes on his first four films, before Anderson’s muse shifted to Jonny Greenwood. The contrast in style is vast, between Brion and Greenwood. And the films are vastly different as well. Anderson has many collaborators, and they all seem to play a part in how a film looks. Which is pretty amazing, if you think about it. Another Director by the name of Anderson (Wes) has frequent collaborators as well, but his tend to just mold themselves into Wes’s style and vision, whereas PT’s collaborators have a bigger impact on the creative output. So Paul’s first four movies definitely have a different vibe than the Greenwood films, and the music is a major part of that.

And then there’s the ever-looming presence of Aimee Mann, whose songs help tell the emotional story of this film. We start the movie with her, and we end with her too, with a few other key songs throughout. That continuity lets us know this is all connected, even though it seems random at first.

Of course, it’s all connected. All of it. The past, the present, the future. But how? That’s something PT doesn’t really give us. He gives us vague metaphors and a few philosophical declarations. It’s like he’s found a bunch of pieces of a puzzle. A rich mosaic. But there are a few pieces missing. Enough to where we can’t fully see the picture he’s giving us. And it’s the opinion of this viewer that this is not just a matter of chance. This, please, cannot be that. I think he meant to give us something incomplete on purpose. Or maybe not incomplete. But deliberately mysterious and open for interpretation. Something imperfect. He’s said in interviews that he “wrote from the gut” on this movie, and the success of Boogie Nights allowed him to have a freer reign over the end product (specifically it’s length). Maybe this movie would be better if he’d cut out like half an hour. Maybe we didn’t need the montage of characters actually singing the soundtrack song in a musical-esque way. But you know what? Who does that kind of thing anymore? It was a bold, risky move. And it actually kind of works, in spite of its awkward earnestness.

The strange thing about this movie is that it doesn’t feel like his other movies. Part of that is due to his shifting cinematic focus. He changes with each new film. So I suppose you could say this about any of his movies. But there are still a lot of similarities between his other films. Hard Eight and Boogie Nights also had ensemble casts with interwoven narratives, but those lacked the ruminations on chance and fate that we get in Magnolia. For his next movie, Punch Drunk Love, he narrows the point of view down to one lovelorn character. It’s a huge departure from all the big themes and magical realist elements that we see in Magnolia. And I guess that’s what’s weird. Magnolia is his only film that dives this far down the metaphysical rabbit hole. Is there a reason for that? Did he just accomplish everything he wanted with this particular style and subject matter, and decide to try new things out going forward? Or was he ready to be done with it, embarrassed by the risks he took?

Magnolia has always been one of my favorites. It’s what really brought me into PT’s world. Even though it’s majorly flawed, I still think it’s one of his most defining artistic manifestations. It’s the movie he just let flow through him, like the essence of his soul being refined down into cellulose acetate. I’m not sure we’ll ever see him return to this kind of film. Which is bitter sweet. But probably for the best. He has other work to do. If he’d stayed in this lane, I don’t think he could’ve sustained his success. Or at least his creative ambition.